One of the reasons Peoria Modern presents local, modern projects is to build a collective appreciation for the works, which leads to people advocating for their preservation. When this doesn’t occur, these works are forgotten.

The following article about a renowned modern residence, recently lost forever, exemplifies that preservation is not easy. It takes people who must first appreciate, then care, to keep the works intact.

The Betty Jayne “represents one of Doyle’s most sophisticated architectural achievements,” AIA wrote in its recognition. “Its carefully orchestrated ensemble of horizontal earth-hugging volumes, large expanses of glazing (including clerestories), and exposed steel elements (including a floating stairway), hallmarks of Modernist design.

Cletis Foley was the quintessential 20th-century modernist architect, ready to throw off the “shackles” of classical architectural dogma and detailing in favor of a sleek, clean and altogether new paradigm that was bold and powerful in its simplicity. Not only did he believe in the beauty engendered by this approach, he also believed in its transformative power to make society a better place.

Richard Doyle was a trailblazing Peoria architect who designed many of the iconic, distinctively beautiful Mid-Century Modern buildings that have defined the Greater Peoria region, from Bradley University’s historic Robertson Memorial Fieldhouse to Peoria Heights’ Village Hall, The Forest Park Foundation Building, Prospect Mall, Peoria Heights Congregational Church, Tower Park and the original Peoria Heights Kelly Avenue Library, now the Betty Jayne Brimmer Center for the Performing Arts.

The Novitiate and Motherhouse campus for the Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, designed and built over a half-century ago, provided a remarkable opportunity to showcase the profound philosophies of 20th Century Modernist Movement. Mister Foley’s design statement above gives a nod to those philosophies at every turn of phrase.

“This place wouldn’t be the same without him.” So said one of Bill Rutherford’s admirers 20 years ago when the Journal Star led off its local “Legacy Project” series chronicling the accomplishments of the “conservationist/lawyer/dreamer” who left an indelible imprint on his hometown ... and on a young man from Spring Bay named Kim Blickenstaff, who would grow up to become an entrepreneur and philanthropist in his own right, continuing in much the same vein as the Rutherford he now calls his mentor.

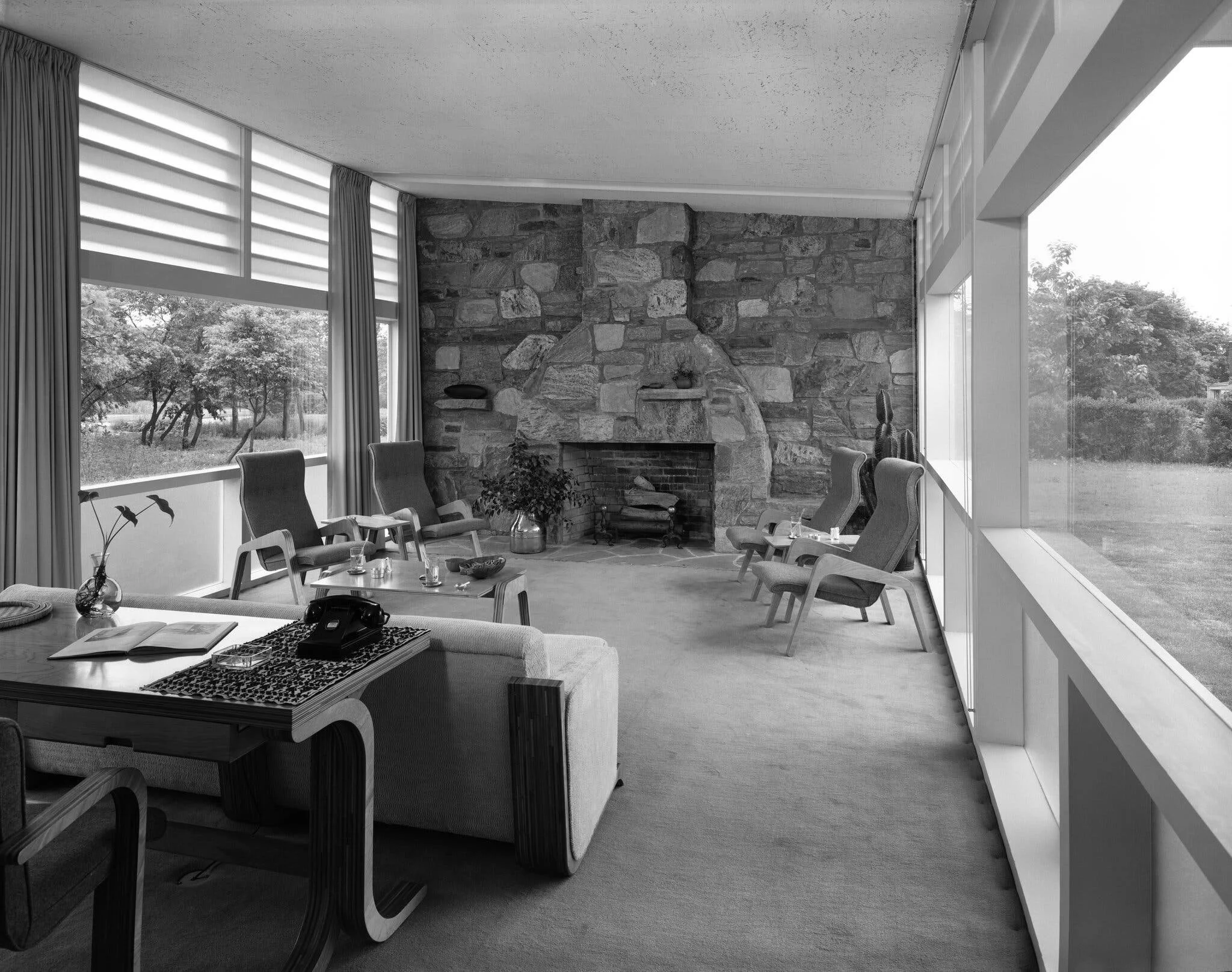

Hazel House was designed by local architect Richard Doyle who, along with his friend, philanthropist William Rutherford, and his wife/partner, Hazel, reshaped and protected much of the scenery and wilderness of the Greater Peoria region for future generations.

Built in 1959, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church energetically reflects Peoria’s mid-century optimism for the future. It is a consummate example of modernist ecclesiastical architecture, designed by St. Louis architect Frederick Dunn. The building reflects Dunn’s movement from art deco to a decidedly modernist approach.

William “Bill” Rutherford was associated for many years with the Forest Park Foundation, which formed Wildlife Prairie Park in the 1960s with an ingenious mission. Rather than being a traditional zoo with exotic animals, it would feature plants and animals native to Illinois, and take visitors back to prairie times. Once again, Peoria was innovating and looking toward the future while honoring the past.

The united spirit of a community shines in the story of the Peoria Heights Village hall, designed by Richard Doyle. The iconic modified A-Frame style Hall with large glass front and adjacent stone walls remains a fixture in the Heights today.

Soon after it was completed in 1982, the Peoria Civic Center became an integral part of this dynamic community. At the time, building the Center was a strategic leap of faith that was based on forward-thinking projections of Peoria.