Modern architecture’s greatest virtue was that it embraced an optimistic, forward-thinking, altogether new way of viewing our built environment.

Peoria Modern is a philanthropic and heartfelt effort to preserve and document for eternity the beauty and wonder that is modernist Peoria architecture and design. The project was designed to showcase great works of modernist architecture throughout Central Illinois in the historical context of Mid-Century Modern design and its roots in optimism.

Masterpieces of Design in Place and Space

One of the reasons Peoria Modern presents local, modern projects is to build a collective appreciation for the works, which leads to people advocating for their preservation. When this doesn’t occur, these works are forgotten.

The following article about a renowned modern residence, recently lost forever, exemplifies that preservation is not easy. It takes people who must first appreciate, then care, to keep the works intact.

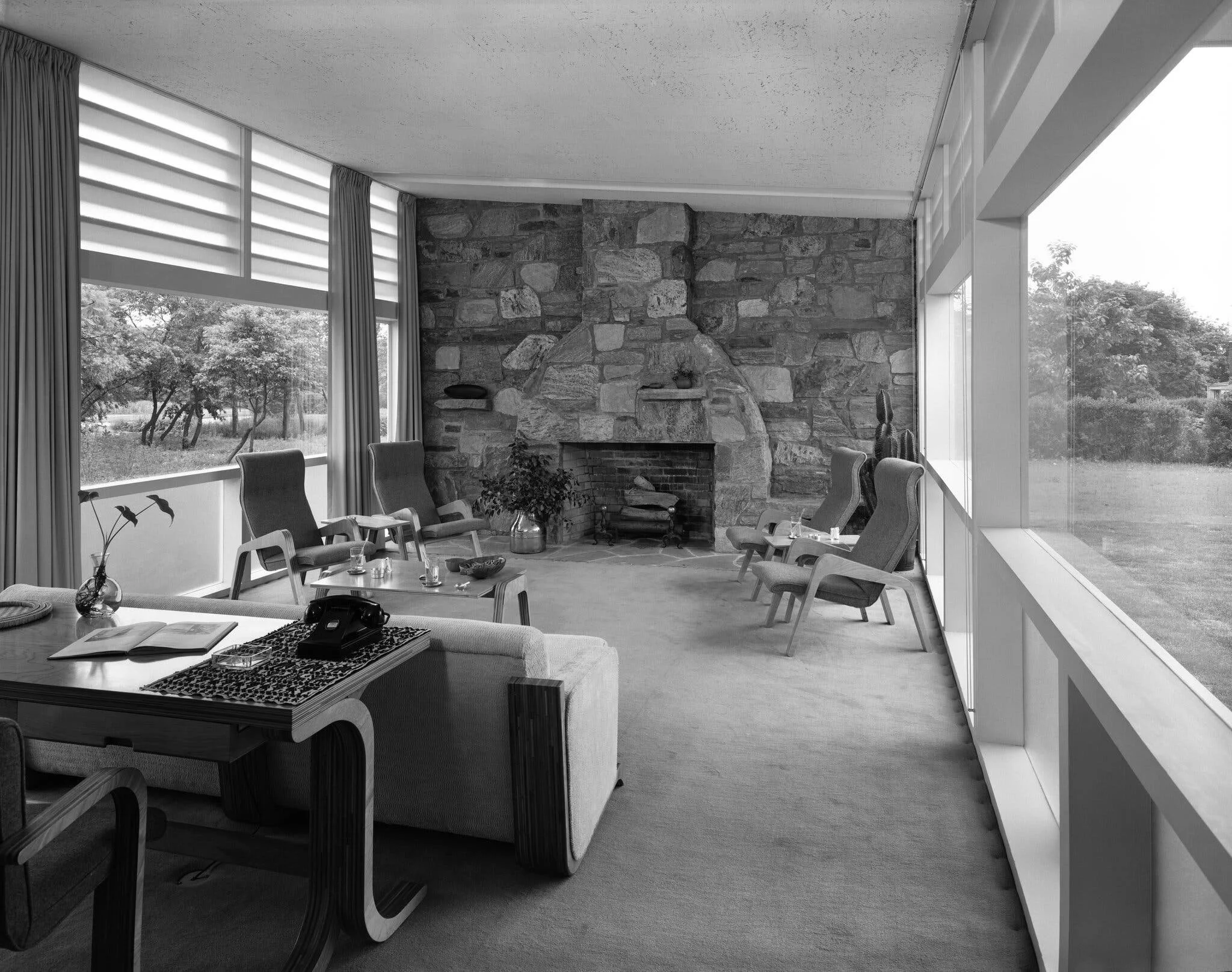

The Betty Jayne “represents one of Doyle’s most sophisticated architectural achievements,” AIA wrote in its recognition. “Its carefully orchestrated ensemble of horizontal earth-hugging volumes, large expanses of glazing (including clerestories), and exposed steel elements (including a floating stairway), hallmarks of Modernist design.

The Novitiate and Motherhouse campus for the Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, designed and built over a half-century ago, provided a remarkable opportunity to showcase the profound philosophies of 20th Century Modernist Movement. Mister Foley’s design statement above gives a nod to those philosophies at every turn of phrase.

Hazel House was designed by local architect Richard Doyle who, along with his friend, philanthropist William Rutherford, and his wife/partner, Hazel, reshaped and protected much of the scenery and wilderness of the Greater Peoria region for future generations.

Built in 1959, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church energetically reflects Peoria’s mid-century optimism for the future. It is a consummate example of modernist ecclesiastical architecture, designed by St. Louis architect Frederick Dunn. The building reflects Dunn’s movement from art deco to a decidedly modernist approach.

William “Bill” Rutherford was associated for many years with the Forest Park Foundation, which formed Wildlife Prairie Park in the 1960s with an ingenious mission. Rather than being a traditional zoo with exotic animals, it would feature plants and animals native to Illinois, and take visitors back to prairie times. Once again, Peoria was innovating and looking toward the future while honoring the past.

The united spirit of a community shines in the story of the Peoria Heights Village hall, designed by Richard Doyle. The iconic modified A-Frame style Hall with large glass front and adjacent stone walls remains a fixture in the Heights today.

Soon after it was completed in 1982, the Peoria Civic Center became an integral part of this dynamic community. At the time, building the Center was a strategic leap of faith that was based on forward-thinking projections of Peoria.